Tagged: 1918 Pandemic, history of medicine, teaching

By Joseph M. Gabriel, Ph.D.

July 28, 2020

This is the second of two posts on teaching the 1918 influenza pandemic, as part of a series exploring the lived experience of Americans during the pandemic. Read the first teaching post here, and read the previous posts in the series by Coyote Shook, Jeff Nichols, Chelsea Chamberlain, and Ann Reid.

In a previous post, I laid out what I see as some of the overarching issues that I think are important to keep in mind when teaching the influenza pandemic of 1918 in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this post I would like to go over some additional themes that I find particularly useful when I discuss the 1918 catastrophe with my students. As in my previous effort, my focus here is on approaches that might be helpful for general history courses that focus on the United States (as opposed to, say, classes on world history or clinically-oriented courses intended for healthcare providers). As will probably become clear, I approach the topic primarily from the perspective of a historian of medicine. I hope this post will help explain how some of the insights from my field can be applied to classes in US history more generally.

One of the basic lessons from the history of medicine is that scientific ideas about disease change over time, sometimes in rather startling ways. Medical and public health approaches to the 1918 pandemic should be understood in this context. One of the central stories in the history of medicine is how over the course of nineteenth and early twentieth centuries disease was increasingly conceptualized as a set of discrete clinical entities that could be identified, tracked, and treated in specific ways. As Charles Rosenberg has argued, before the mid-nineteenth century physicians typically understood disease as growing out of an imbalance in the bodily system that could be caused by a wide variety of factors, such as the weather, strong emotions, or poor habits. As a result there was significantly less sense of disease as discrete “things” that have their own ontological status than there is today. By the early twentieth century, however, disease had been reconceptualized as a collection of discrete and specific clinical entities, each of which had its own unique cause, natural history, and set of symptoms. The development of bacteriology and virology in the late nineteenth century was an important part of this process: the development of both fields was deeply intertwined with the growing assumption that specific diseases could be linked to specific causative agents that, in turn, could be identified and investigated. By the late nineteenth century, then, “influenza” had been conceptually disentangled from other clusters of problems that were given other names, such as “bronchitis” and “asthma.” By this point it was also assumed that a specific cause of the disease could be found, although the virus itself was not actually identified until 1933.

Illustration of Mary Mallon, 1909, The New York American.

One consequence of this broad transformation was the growing concern among public health officials with germs, asymptomatic disease carriers, and behaviors that might spread disease. By the early twentieth century public health initiatives focused on the detection and mitigation of invisible threats and the effort to inculcate healthy behaviors, such as handwashing, among the public. Not surprisingly, these efforts often overlapped with xenophobic concerns about immigration and with racist stereotypes about racial and ethnic minorities—including, notably, nativist concerns about Chinese and Eastern European immigrants. The story of Mary Mallon is a key example of this dynamic—Mallon was an Irish immigrant and the first asymptomatic disease carrier identified in the United States. Between 1907-1910 and 1915-1938 she was incarcerated in a hospital in New York City after working as a cook and infecting numerous people with typhoid. A significant amount of material related to Mallon’s case is easily accessible online. Her story can be used to place the influenza pandemic in the context of ongoing concerns about other diseases and to raise questions about public health efforts to regulate behavior, the developing fears of asymptomatic carriers, and the long history of blaming racial and ethnic minorities for disease. Indeed, given this long history, the relative lack of xenophobia directed against immigrants in the 1918 pandemic is striking. Crucially, Mallon’s story can also be used to raise questions about why some people continue to engage in dangerous behaviors even if they risk infecting others. In her case, the answer is simple: she had to work to support herself.

Although some public health efforts did take place at the state and federal levels, before World War II most took place at the municipal level. Cities thus responded to the 1918 pandemic by instituting a series of policies that students will find familiar, including mandatory mask wearing, canceling events, school closings, and what we now call “social distancing.” One of the key lessons here is that different cities responded with different degrees of urgency and, as a result, the populations of different cities suffered at different rates. The best-known example is the difference between St. Louis and Philadelphia, with the former quickly instituting mitigation strategies and the latter delaying and, as a result, suffering significantly more deaths. This was a general phenomenon: as Howard Markel has recently explained, in 2006 researchers affiliated with the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan extensively studied the 1918 pandemic and concluded that varying implementation of non-pharmaceutical mitigation strategies led to significantly different results among a wide variety of cities. Markel and his colleagues also identified communities that had relatively few, if any, influenza cases. Their website provides case studies of these communities along with selected primary documents. Interestingly, their study became one basis for the Center for Disease Control’s pandemic response plan. Whether or not their recommendations have been followed in the current crisis would make an interesting discussion point for students who want to think seriously about the relationship between past and present.

Aircraft hull travels the parade route during the 1918 Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade.

In addition to the public health response, students might be interested in the way that physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers responded to the 1918 pandemic. Images of field hospitals, bodies being loaded into ambulances, and other scenes are easily available and provide compelling visual evidence of the tragedy. Not surprisingly, different groups of actors responded in different ways to the crisis, and these responses can be used to discuss gender, racial, class, and other dynamics as the disaster unfolded. Nancy Bristow, for example, has argued that for the overwhelmingly female nursing profession, the epidemic provided “a meaningful opportunity for service that only enhanced their confidence as women and as nurses,” as opposed to the male-dominated profession of medicine, which was largely powerless in the face of the disease. Nurses associated with the Red Cross played a particularly important role in the pandemic response, as did female caregivers who took care of the sick and dying in their homes. Discussions about the racial and gender dynamics of nursing in the 1918 pandemic can then be used to raise questions about the status of “essential workers” in the labor force today.

The failed effort to develop an effective vaccine in 1918 may also be of interest to your students. In what historian John Eyler has called “the fog of research,” medical researchers quickly developed a wide variety of vaccines once the pandemic hit and instituted vaccination programs under the belief that these new interventions worked—only to later discover that they did not. This was, in part, due to the fact that virology was simply not yet up to developing an effective pharmacological intervention for influenza. Virology was still a young field (the first virus had only been identified in 1892), and the isolation of the influenza virus did not take place until 1933, with the identification of different types and the first effective vaccines not coming until the 1940s. As Eyler discusses, the mistaken belief that newly developed vaccines were effective also reflected the disjointed nature of clinical drug trials at the time and the lack of standard protocols such as blinding that we now take for granted in clinical research. The failure to develop a vaccine in a timely manner can thus be a useful rejoinder to the assumption that we will soon have a vaccine for COVID-19—hopefully we will, but the jury on the issue is still very much out. It can also be used to shed light on the ongoing history of clinical drug trials and to raise questions about the relationship between science and politics, the role of funding sources in developing new cures, and other dynamics that are often ignored in discussions of scientific breakthroughs and heroic narratives of “wonder drugs” and “magic bullets.” Perhaps most importantly, this topic can be used to raise questions about the immense resources we now devote to medicine and the development of new pharmaceuticals, problems with our drug development system, and the relative lack of funding for public health.

San Franciscans waiting in line for masks to prevent the spread of influenza, 1918, California State Library.

One obvious topic that should prove interesting to students is popular resistance to both public health measures and medical authority. Efforts to implement non-pharmaceutical mitigation strategies led to intense public debate, with many citizens seeing public health mandates as a form of tyranny – in San Francisco, for example, the Anti-Mask League loudly opposed the city’s mask-wearing ordinance. These types of public debates overlapped with the long history of anti-vaccination (and anti-inoculation) movements and with American political and cultural traditions more broadly. As one critic in San Francisco put it, “If the Board of Health can force people to wear masks, then it can force them to submit to inoculation, or any experiment or indignity.” It is important to remember, though, that there were scientific questions at the time about how to best respond to the crisis that entered public consciousness—in December of 1918, for example, the California Board of Health declared that the flu was not dangerous enough to warrant the inconvenience of wearing masks. Helping students understand the contours of the complex debates about masking and vaccination in the early twentieth-century provides numerous opportunities to think about similar dynamics today, including the messy nature of scientific deliberation, the way in which science and politics are intertwined during moments of crisis, and the sources and consequences of public trust and distrust in medical authority. They can also be used to discuss the manner in which historical narratives are deployed for political purposes.

I also think it is helpful to make clear to students that the 1918 pandemic was one particularly catastrophic episode in the long history or humanity’s struggle with disease. This is true in the narrow terms of the history of influenza: there have been five pandemics in the last 130 years (in 1889, 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009), and while the others were less severe they were still significant events—the 1957 pandemic, for example, killed about 116,000 people in the United States. More broadly, influenza is of course only one disease, and contextualizing the 1918 pandemic in the context of other diseases and epidemics helps students understand it as something more than a horrible one-off event. It might also be helpful to contrast the different public responses to endemic disease and other health problems that are a constant presence in society—and therefore attract relatively little public concern—and the dramatic nature of sudden epidemic outbreaks. Particularly relevant in this regard is the emergence and continued toll of HIV/AIDS. What was once understood as an urgent crisis has receded from public consciousness even as the disease continues to take a horrible toll. Influenza is itself an example of this dynamic—a fact that has been successfully politicized by those who point to its continued lethality as a way of downplaying the dangers of COVID-19.

Members of the American Red Cross remove a victim of influenza from a house in St. Louis, Missouri, 1918, St. Louis Post Dispatch.

A related issue is the continued threat of novel viruses. Discussing the emergence of a new influenza virus in 1918 and the catastrophic events that followed can help students understand the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 as part of an ongoing process in which novel viruses emerge and occupy evolutionary niches comprised of immunologically naïve hosts. Recent examples include the Ebola virus (which first emerged in 1976), H5N1 (a particularly lethal subtype of avian influenza with the first known human cases appearing in 1997), the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV (which appeared in 2003 and is sometimes now referred to as SARS-CoV-1), and a new strain of H1N1 that moved from swine to humans and caused a relatively mild pandemic in 2009. Public health authorities have been tracking the emergence of dangerous new viruses for decades. They have also been issuing warnings about their deadly potential for equally as long. Placing the 1918 pandemic in the context of more recent concerns about novel viruses helps make clear that the threat of another truly catastrophic global pandemic was well-known long before COVID-19 upended the world. It also makes clear that the worst may be yet to come.

Finally, you may want to discuss issues related to commemoration, mourning, and how the widespread suffering that followed in the wake of the 1918 pandemic was memorialized. Or, perhaps, how it was not. The 1918 catastrophe is sometimes referred to as the “forgotten” pandemic due to the fact that there was relatively little public commemoration of the dead at the time and, until quite recently, the event itself seems to have been largely forgotten in our historical memory. This has parallels to today that are worth exploring—why was there relatively little public mourning in 1918, and why is there so little public mourning today? Why do textbooks of American history devote so little time to it? Why is there simultaneously a seemingly endless flood of news about COVID-19, yet little attention from our elected officials about the devastating suffering that so many of us are experiencing? What are we to make of mass graves, then and now? Of course, people in 1918 recorded their experiences in their diaries and letters. They memorialized their loved ones at their funerals and on their gravestones. In doing so, they sought to capture and preserve their experiences. At times, these experiences were used as the basis for powerful works of literature that could be used in our classes. More often, though, their memories have been forgotten. It is worth asking our students: is this what will happen to our stories as well?

Digging a mass grave in Philadelphia to bury victims of influenza, the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Perhaps. For the moment, though, capturing our own stories and sharing them with others can help us make sense of our experiences. Once my classes were moved online this past semester I gave my students the option of replacing their research paper with a narrative about their experiences with COVID-19 and what, if any, parallels they saw with the themes we had been discussing in class. I believe that this was a useful exercise for my students, and it was powerful for me to read their stories. One student told me about the collapse of his family’s business, and how they did not have the money to pay their mortgage. Another told me about his guilt at having celebrated during Spring Break and the possibility that he helped spread the virus. A third told me about her family member who died alone in a hospital because no visitors were allowed. I strongly encourage everyone who is planning on teaching the 1918 influenza epidemic to incorporate some type of self-reflective exercise for their students about their experiences with COVID-19. It is a powerful way to make the case for the continued relevance of the past. It may also help you, and your students, make some sense out of these terrible times.

Joseph M. Gabriel is Associate Professor in the Department of Behavioral Science and Social Medicine and the Department of History at Florida State University. He studies the history of medicine, with a focus on the history of pharmaceuticals and the pharmaceutical industry. He is the author of Medical Monopoly: Intellectual Property Rights and the Origins of the Modern Pharmaceutical Industry (Chicago, 2014) and co-editor of Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Pittsburgh, 2019).

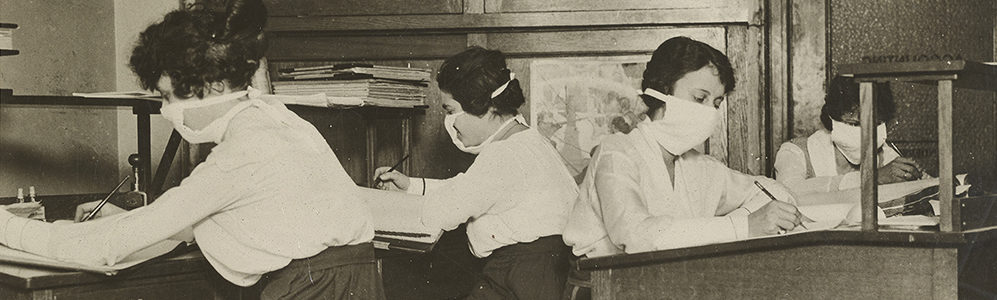

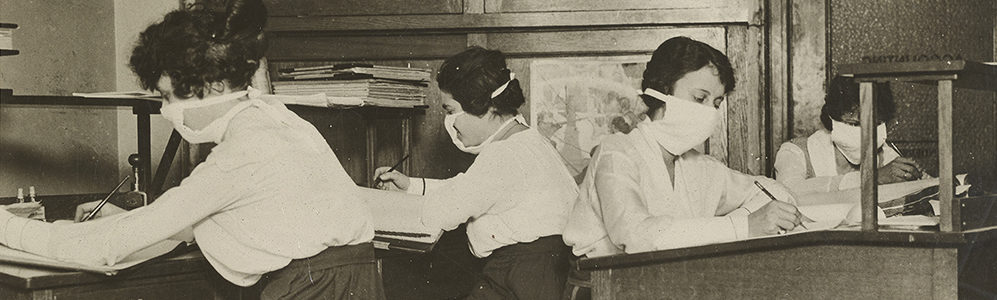

Cover Image: Clerks in New York City wearing masks at work. National Archives Identifier 45499337.

Receive a year's subscription to our quarterly SHGAPE journal.